- first, the relative probabilities that students from different types of school got "very strong GCSEs"; ranging from 3.4% for a student from the poorest tenth of schools, to 23.4% for those from independent schools;

- second, the probability that a student from each type of school who got "very strong GCSEs" did in fact apply to Oxford at all, ranging from 14.1% to 24.6% (even higher for pupils from the richest tenth of state schools;

- third, the probability that such a student who did apply got admitted - over half for pupils from independent schools, but only about 15% for students from the poorest schools.

So there were disparities at each stage of the process. Students from state schools in poor areas were less likely to get very good GCSEs, less likely to apply, and less likely to be accepted. Not surprising; but what surprised me was the interpretation of the results. Chris concluded

"The FT’s analysis supports the view held by elite universities that the problem lies largely not with universities but in the school system."This is undoubtedly correct, so far as it goes. But Wendy Piatt, Director General of the Russell Group, seems to think that Oxford is entirely off the hook:

“Even when poorer students get the right grades they are much less likely than their wealthier peers to apply to top universities. We cannot offer places to those who do not apply.”

But that's just not what the data show. What it shows is that a student from one of the poorest schools who gets the right grades is a little more than half as likely as an independent school student to apply to Oxford. That's bad. But a student from one of those who does actually apply is less than a third as likely to be accepted. That is worse. And what is even worse is that Ms. Piatt and the Russell Group don't seem to accept that there is a problem. Eliminating the disparity in acceptance rates would more than triple the number of well-qualified applicants from the poorest tenth of schools attending Oxford.

The Russell Group's refusal to engage with the issue isn't just a matter of an off-the-cuff quote to a newspaper either; their submission to the Commons Select Committee takes the same line, arguing - accurately enough - that

Of course these data alone don't tell the whole story (as Chris was careful to emphasise); perhaps,even among those getting "very strong GCSEs", independent school pupils are better qualified, or applying for easier courses. And there might be something odd about the applicants from the poorest tenth of schools - although even if you look at the bottom three deciles of schools, applicants are still only half as likely as those from independent schools to be admitted. The Russell Group's refusal to engage with the issue isn't just a matter of an off-the-cuff quote to a newspaper either; their submission to the Commons Select Committee takes the same line, arguing - accurately enough - that

The most important reason why too few poorer students even apply to leading universities is that they are not achieving the required grades at schoolbut simply ignoring the admissions disparity; even though that is the one thing that is actually under their direct control.

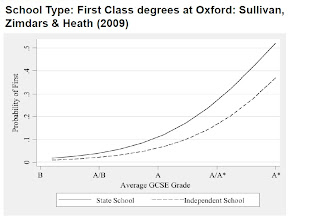

On the other hand, there is surely a strong argument that the innate ability of a pupil who, coming from one of the poorest state schools, still manages to get very strong GCSEs and apply to Oxford, is likely to be rather greater than a similarly qualified independent school pupil. And indeed there is statistical evidence that the second effect appears to dominate; as this study, coincidentally also about Oxford, found:

Private school students perform less well in final examinations relative to their GCSE results when compared with state school students

This is represented very clearly on this chart:

So in other words, students from state schools who apply to Oxford are much less likely to get in than those from independent schools with the same grades; but if they do get in, they'll probably get better degrees. This is not news - it was true when I attended Oxford a quarter century ago, so they've had plenty of time to deal with it.

So it is in the light of the data above that we should read articles like this in the Telegraph, that claim that efforts to reduce this disparity are "social engineering"; or reports like this, from the "Fair Access to University Group", which simply assert without looking at admissions data that "it is clear that the problem lies not in universities’ admissions policies".

In fact, what the data and evidence suggest is that Oxford is already, and has been for some time, engaging in "social engineering" in favour of private school pupils. It has an admissions process that favours them and admits them even though they are less likely to get good degrees. Reversing that might or might not constitute further "social engineering" but the evidence suggests it would improve not only make Oxford less socially exclusive, but more rather than less meritocratic. (To be fair, I should note that Chris, who is much better informed on this than me, thinks that Oxford is now genuinely focusing on some of these issues).

So it is in the light of the data above that we should read articles like this in the Telegraph, that claim that efforts to reduce this disparity are "social engineering"; or reports like this, from the "Fair Access to University Group", which simply assert without looking at admissions data that "it is clear that the problem lies not in universities’ admissions policies".

In fact, what the data and evidence suggest is that Oxford is already, and has been for some time, engaging in "social engineering" in favour of private school pupils. It has an admissions process that favours them and admits them even though they are less likely to get good degrees. Reversing that might or might not constitute further "social engineering" but the evidence suggests it would improve not only make Oxford less socially exclusive, but more rather than less meritocratic. (To be fair, I should note that Chris, who is much better informed on this than me, thinks that Oxford is now genuinely focusing on some of these issues).

None of this is to understate the supreme importance of improving outcomes for poor pupils in state schools long before they get anywhere near university; Chris, the Russell Group, and the Fair Access to University Group are all correct that this matters more than anything else. But simply denying there is any problem at all with elite universities' admissions, as Ms Piatt does, or arguing that any pressure exerted by government on those universities to do something about it is "social engineering", as the Telegraph and the Fair Access to University Group do, misses the point. The admissions status quo is bad for both the UK's best universities and bad for bright pupils from poor backgrounds.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.